New publication about the knallgas bacterium Cupriavidus necator

·What exactly is a ‘knallgas’ bacterium? The word ‘knallgas’ is of German origin and simply means a mixture of hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) that can violently react to water (H2O) when ignited (‘knall’ means explosion). In this chemical reaction, the energy-rich and reactive hydrogen molecule donates it’s electrons to the di-oxygen molecule which is highly oxidized and craving for electrons. This is a classical ‘redox’ (reduction/oxidation) reaction, because both processes are coupled and involve an electron transfer. So what have bacteria to do with this? Usually nothing, except for some rare species that can consume raw hydrogen directly as a kind of personal jet fuel. One of these bacteria is Cupriavidus necator aka Ralstonia eutropha, which we have studied in a new publication that just came out in eLife.

A versatile metabolism

Cupriavidus is an otherwise unassuming pale-yellow soil bacterium, but it’s metabolic flexibility shines! It can grow on no less than 200 different carbon and energy sources, among them several very toxic compounds that found in gasoline. It can also cope with a lot of different environmental stresses using the genetic tools it has at hand to degrade toxic compounds, pump out antibiotics, and other means of stress resistance. For comparison, it’s genome is around 50% larger as that of the model organism E. coli (6,600 vs. 4,300 genes), and many of the often hypothetical genes seem to be transporters, highlighting again its strong association with its environment.

Open questions

This bacterium and its ability to use hydrogen as energy source has been known for a while. It is also known that Cupriavidus can fix CO2 just like plants do, using a biochemical pathway called the Calvin cycle. Not enough, this bug is also the prime model organism for the production of bioplastics (polyhydroxybutyrate), of which it can accumulate large amounts. But what really interested us was its metabolic flexibility. While many bacteria are solely adapted to one particular environmental niche, this bacterium seems to be a genuine generalist. As such, we wondered how many of its genes are actually expressed (translated into proteins) and utilized in different trophic conditions. To answer this question, Cupriavidus was cultivated on different substrates (fructose, succinic acid, formic acid with CO2 fixation) and with different strengths of limitation. We then analyzed the proteome using mass spectrometry and used a detailed computational model to predict which proteins are really utilized and which are simply idle.

Cupriavidus is adapted to a lifestyle in changing environments

Here is a point by point summary of our findings.

Finding 1

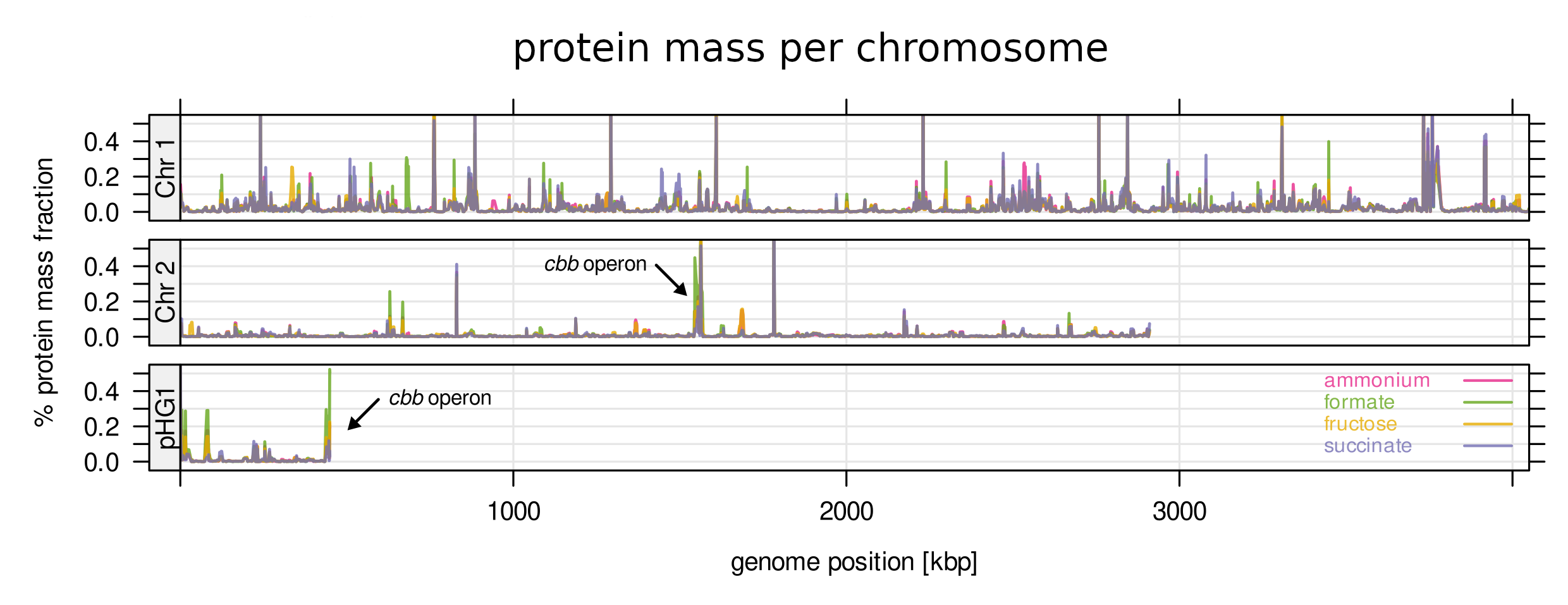

Cupriavidus’ genome is organized in three different chromosomes, two larger and one smaller often termed a megaplasmid. Using MS we quantified its proteome at unprecedented depth. We found that almost all protein mass (79%) is encoded by chromosome 1. Chromosome 2 and the megaplasmid pHG1 encode only 16% and 5%, respectively. It turned out that gene expression for chromosome 1 is more invariant across many conditions, while expression of chromosome 2 and pHG1 is regulated on demand. This supports the hypothesis that chromosome 1 is the original DNA molecule and chromosome 2 and pHG1 were acquired more recently in the evolution of this bug.

Finding 2

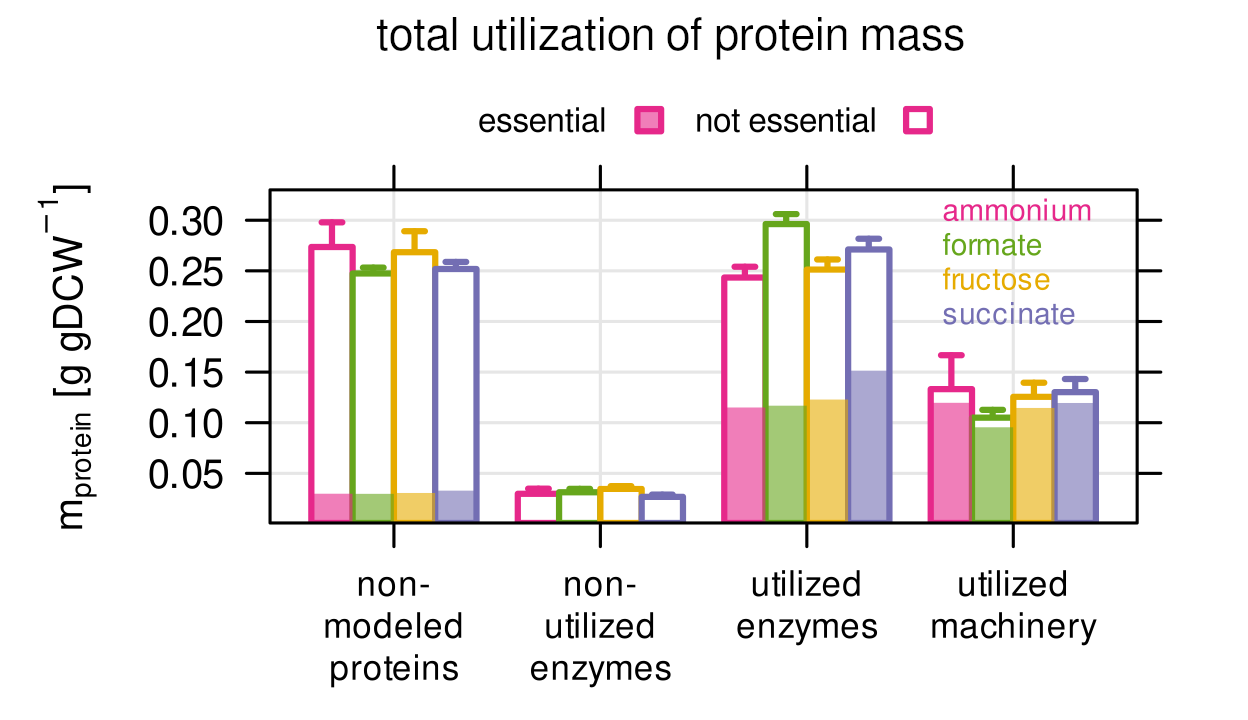

We constructed and trained a genome scale resource balance analysis (RBA) model that can not only predict metabolic flux, but also enzyme demand and utilization. We found that more than 50% of protein mass is utilized, but the same amount of (mostly uncharacterized) protein mass is not. The utilized protein mass is concentrated on a small number of often essential genes. Only 93 genes responsible for transcription, translation and DNA replication make up 20% of the protein mass.

Finding 3

We did not only test if enzymes are utilized or not, but also quantified the degree of utilization. We found that highly utilized enzymes are significantly more abundant, less variable across different conditions, and more often encoded by an essential gene.

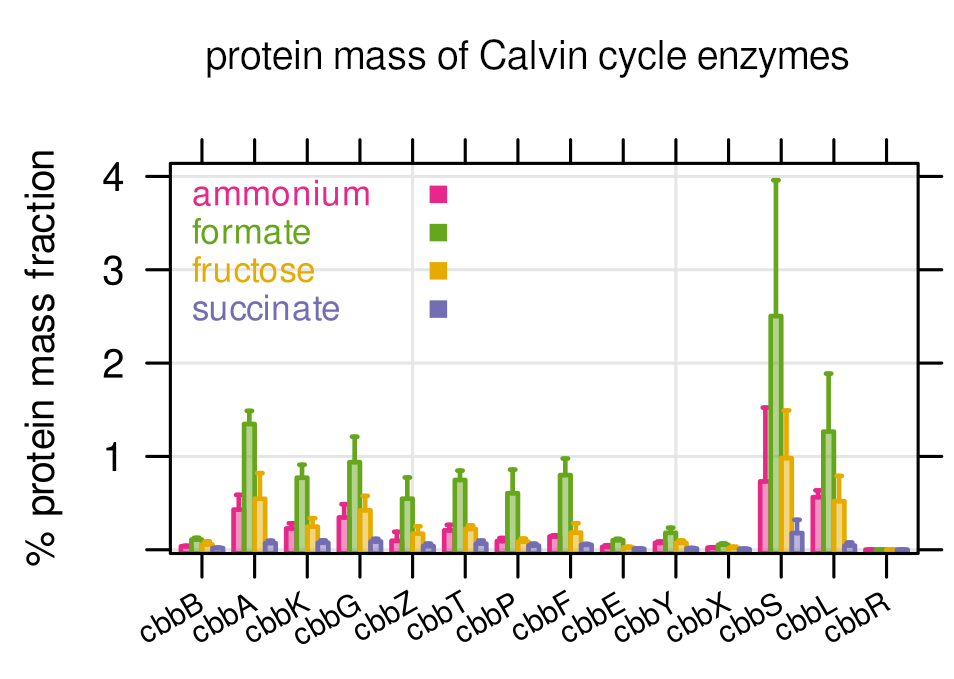

Finding 4

Calvin cycle enzymes (used to fix CO2) are heavily expressed on formic acid, but also on fructose where they should not have a benefit. The predicted utilization on fructose was poor. This led to one of the most exciting questions in our paper: Can C. necator re-assimilate already emitted CO2 to increase its overall biomass yield?

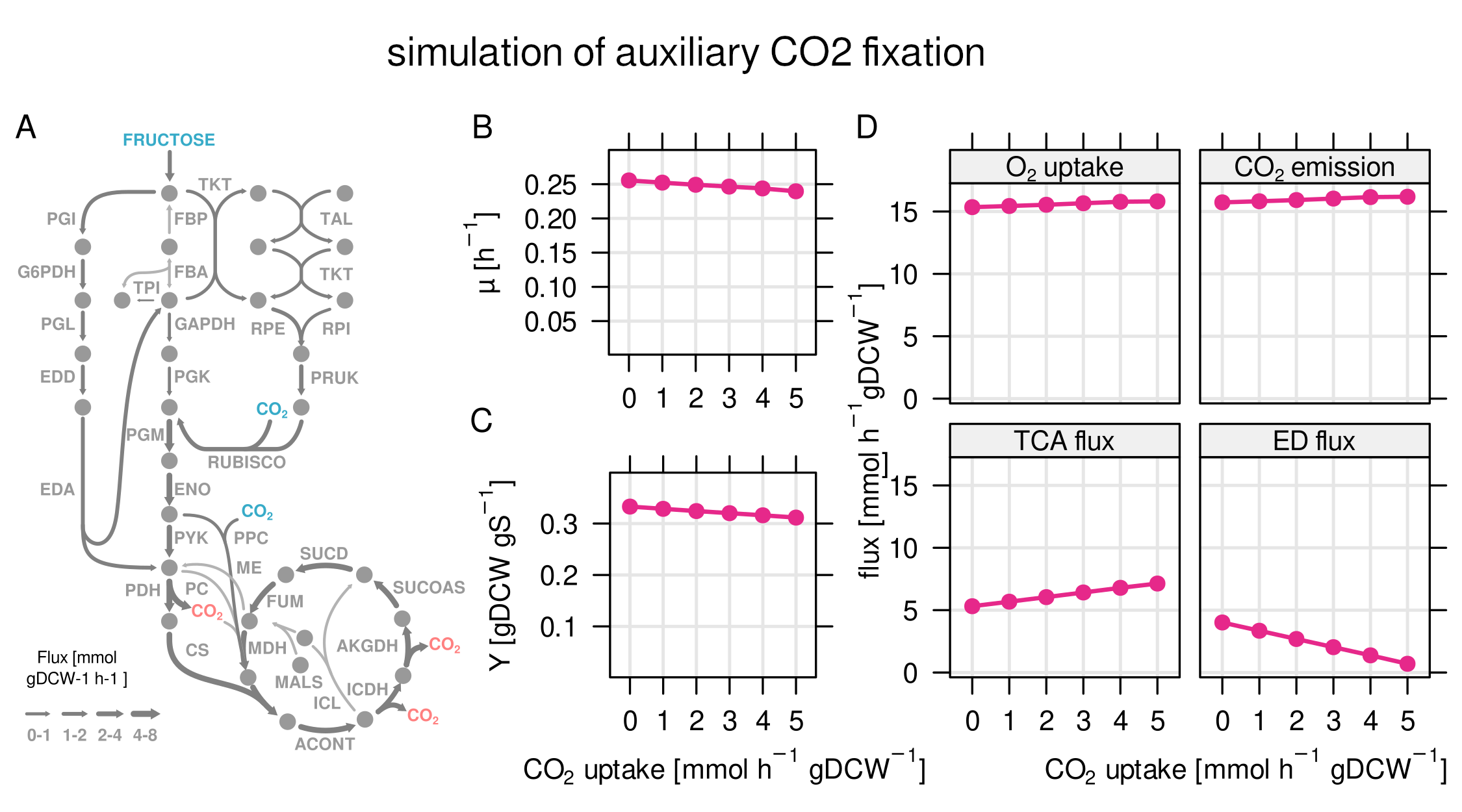

Finding 5

To answer this questions, we simulated growth on fructose with additional CO2 fixation through the Calvin cycle using the RBA cell model. According to the predictions, auxiliary CO2 fixation will not increase growth, yield, or the amount of total fixed carbon, due to the high energy cost of the Calvin cycle.

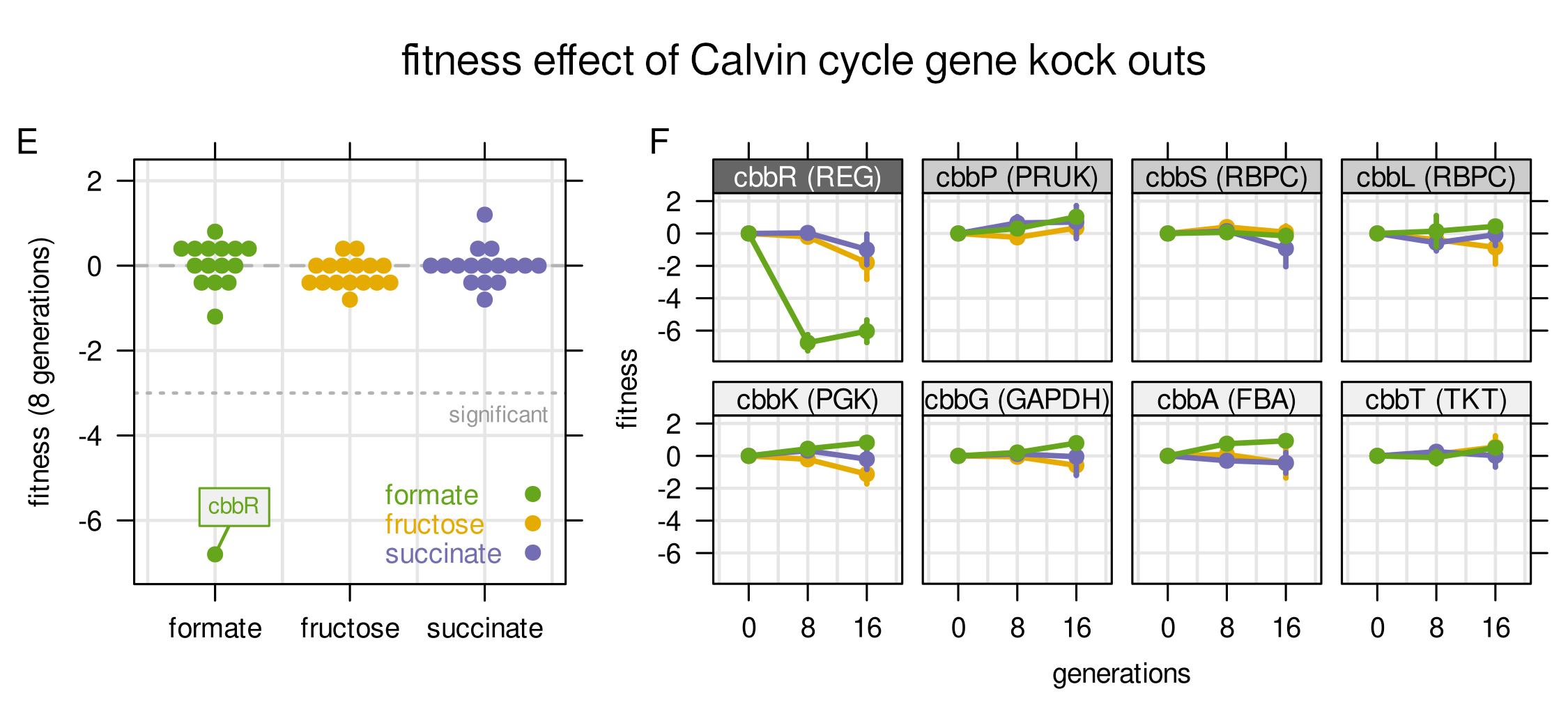

Finding 6

To validate experimentally that CO2 re-assimilation on fructose has no growth benefit, we cultivated a 60,000 mutant KO library on different substrates. It turned out that the KO of Calvin cycle enzymes was neutral to growth, except on formic acid where CO2 fixation is essential (cbbR). This means that auxiliary CO2 fixation did not provide a (clear) growth benefit on fructose. Instead, we propose that C. necator is adapted to a lifestyle of ever changing environments, making constant readiness for new substrates a successful strategy.